Two books dealing with conflict shed light on these divisive times.

We’re arguably living in one of the most divisive times in recent history, and violent nationalist language has steadily been creeping out from the dark corners of the internet, confronting us with violent deaths, hate crimes, and college students giving the Nazi salute. And while man-made borders have exacerbated violent rhetoric, they certainly don’t confine it.

For centuries, literature has helped us make sense of conflicted times, acting both as documentation and as a critique to work through the moral complexities facing society. This month we’re reading two stories dealing with issues of race, immigration, and the violence that emerges when we think of people as “others.” Although each book deals with conflict unique to their countries of origin, they both share a similar narrative structure of oral tradition being transcribed into writing, ultimately placing the onus on writers to transcribe a society in transition and turning a global story into a personal struggle. – Meghan Udell

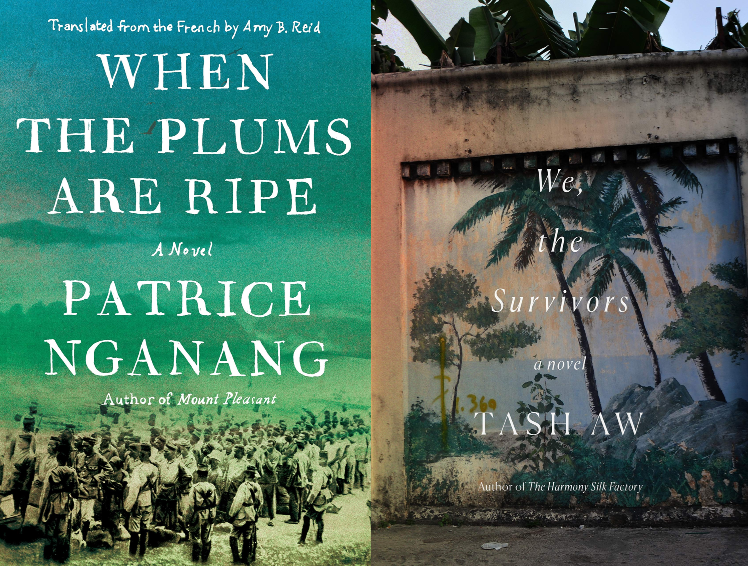

When the Plums Are Ripe, by Patrice Nganang

Set during the years between the Vichy France defeat and the subsequent resistance led by Charles De Gaulle, Pouka, a Cameroonian poet, tells the story of his country’s forced involvement in WWII. After a French education in the capital city of Yaoundé, Pouka returns home to Nazi occupied Cameroon to bring the gift of poetry to his village much like his idol Théophile Gautier. There he assembles a team of wanna-be poets who, one-by-one, are called off to fight for Free France.

As his family and friends meet their untimely end against a backdrop of racism and imposed European nationalism, Pouka escapes the worst of the brutality of war, but is forced to serve as a lyrical scribe detailing the violent deaths of his circle of poets. Throughout the story, Nganang uses the perfectly apt metaphor of discarded ripe plums — a Cameroonian delicacy — to confront the troubled history of French colonialism, and to call into question our uniquely western understanding of global conflicts.

“His story would sit just below the surface of the murky water of the tilapia farm he manages if it weren’t for the fact that a simple phone call sets in action a course of events that lead to the murder of a Rohingya immigrant.”

We The Survivors, by Tash Aw

Our second book jumps across continents and time to land in present day Malaysia, telling the story of Ah Hock, the son of Chinese Immigrants as he navigates a rapidly changing Asia. The thing most striking about Hock, the main character in Tash Aw’s We The Survivors is his complete lack of remarkableness. In a stark contrast to Ngannang’s Pouka, Ah Hock is an ordinary man whose struggles are no different than any other working class immigrant. In fact his story would sit just below the surface of the murky water of the tilapia farm he manages if it weren’t for the fact that a simple phone call sets in action a course of events that lead to the murder of a Rohingya immigrant.

After his release from prison, Hock recounts his crime for Su-Min, a US educated sociology postgraduate, who has returned to Malaysia to write a book about his case. Class and race inequalities take front and center stage in his wandering narrative, with each turn leading Hock further away from the life he envisioned, and closer to the inevitable crime.

Told in a non-linear fashion, Hock leads both the reader and writer on a journey through his life, from his childhood in a small fishing village raised by a single mother, and back to his happier adult life pre-murder. Throughout the narrative, we’re struck by the notion that the smallest of choices can have drastic impacts. At any step along the way, Hock could have simply changed course, except that with success always just out of reach, he has nowhere to go but through.

Both of these stories ring especially true in today’s culture of demanding immigrants — and those viewed as “others” — be exceptional, before being considered worthy of acceptance into a new society. It’s a rhetoric that feels both ubiquitous across cultures and uniquely American, tying into the myth that perseverance and hard work alone allows people access to the American dream.

Purchase When the Plums Are Ripe with a 20 percent discount here.

Purchase We the Survivors with a 20 percent discount here.