Serenaded by Nina Simone and an artist’s journey through the mind’s wild frontier

By Aaron Hicklin

Among the pleasures of running a small town bookstore is not just the stories surrounding you but the stories that walk through the door. It’s a cliche to say that everyone has a book inside them, and in less charitable moments I think of Christopher Hitchens who added a caveat: “Everybody does have a book in them, but in most cases that’s where it should stay.” But I trained as a reporter, and I interview people for a living, and despite my restless, impatient nature I have (mostly) learned to listen for stories when the opportunity presents itself. Often it’s when I least expect it, or feel most tired or irritable, that a routine pleasantry turns into the kernel for a story or recollection that scrambles my preconceptions.

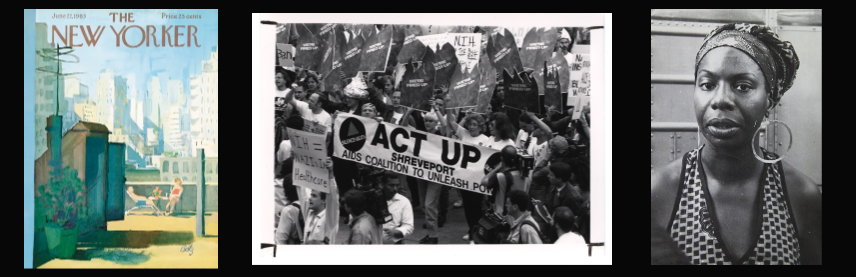

Take Ellen Bay, a customer in her late 70s who came in one recent weekend to order a book on the famous street photographer Bill Cunningham. After a few observations on our narcissist-in-chief, we landed on the current plight of New York City’s hospitals. I happened to mention St. Vincent’s hospital in Chelsea (now a luxury condo, natch) and the frontline role it played during the AIDS crisis, only to realize that Ellen didn’t need history lessons from me. She’d been an active member of the AIDS coalition, ACT UP, in the 80s and 90s, including protests inside St. Vincent’s. She knew Larry Kramer, and had opinions. It’s commonplace to see casual insults directed at Boomers on social media, and Ellen reminds me why I find them so aggravating. They serve to erase stories like hers, boxing an entire generation into a set of lazy assumptions and reductions. Stories are how we bridge the divide, but first we need to listen to them.

When Ellen returned for her book a week later, she conjured an image of her 20-year old self, answering phones at The New Yorker, and quietly working on a submission that Brendan Gill helped steer to publication in 1963 (you can find it here between ads for vacations in Jamaica and fresh Maine lobster). Ellen had other stories, too, including a thankless escapade around New York hunting white nail varnish for Nina Simone (she was producing her show at Newark’s Symphony Hall). Ms. Simone had a reputation for being testy, and Ellen did not contradict it, but then came a tale of utter grace. In the car Ms. Simone asked Ellen’s colleague (and future husband) to name a favorite song. He chose a track by Leonard Cohen. Unbidden, Simone began to sing it. Imagine it! Undone by that powerful voice, he stopped the car and wept. Although it’s easy to become jaded by humanity’s infinite capacity for stupidity and greed, small daily interactions like these constantly remind me that everyone’s life is a narrative filled with triumph and tribulation, comic interludes, griefs small and large, and moments of reprieve.

Something else you discover when you run a small bookstore like mine: almost everyone has a talent that illuminates who they are. A young boy, Arthur, who comes in annually to spend his birthday money on books, turns out to be the most incredible graphic artist with a wild and loose imagination; an opera singer, with a passion for preserving the legacy of composers murdered in Theresienstadt, once demonstrated her pipes by singing an aria in the store; a former schoolteacher is also an expert ice cream maker. When I first conceived a literary festival for Narrowsburg, most of those who ended up participating were initially customers who walked through my door (ice cream maker and opera singer included). I kept telling people that some divine synergy was at work, but of course synergy was just another word for community. We are all part of a community, but from the intimacy of a bookstore the sheer richness and vitality of a place, even a tiny one like this, achieves a beautiful clarity.

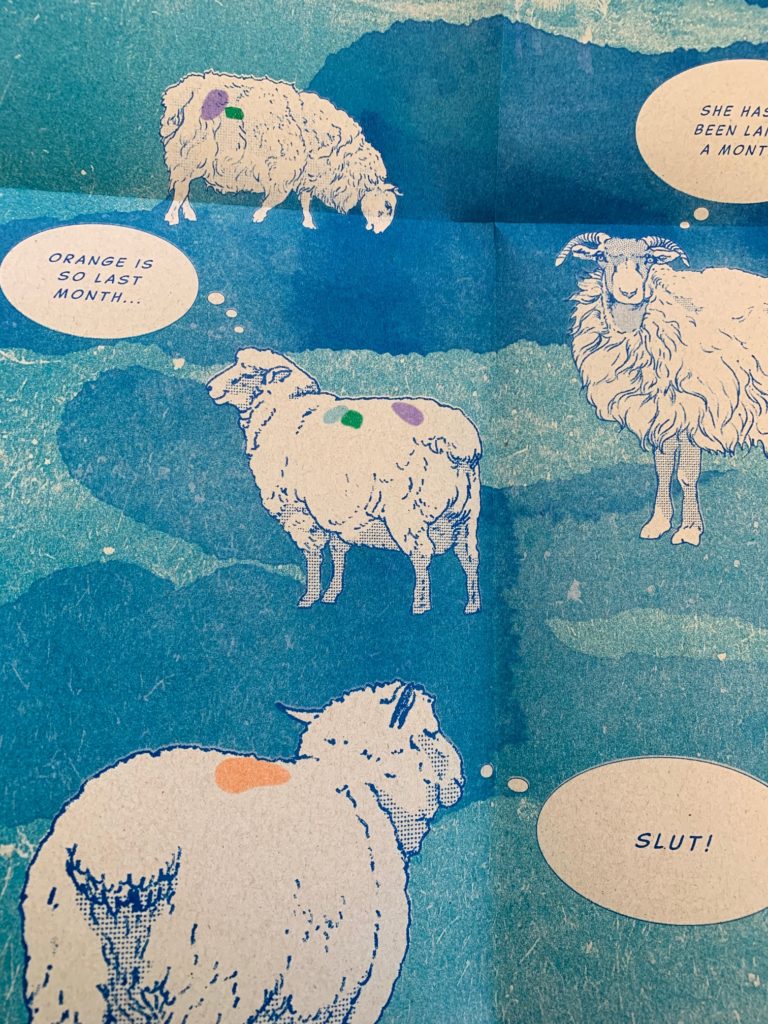

I don’t recall when Dasha Ziborova first visited the store, or what she brought, and neither does she (although she thinks she probably picked up Marlon James’s Book of Night Women or Stupid Model by local author Barbara de Vries), but what I do remember is her bright and generous energy. When such a person enters a bookstore, it can feel like a hit of dopamine. It was a good deal later that I discovered she was an artist and comic book creator, one with a dream-like eye for oddity. One of her comics is titled Sex Life of Sheep, based on a visit she made to the Scottish Highlands; another, Lesson 21, focuses on her experience of school in the Soviet Union; she graduated high school just as Mikhail Gorbachev came to power. “You wouldn’t believe how, in two or three years, everything changed,” she recalled during a recent conversation. “It was so rapid, but when I was growing up communism seemed like it was forever.”

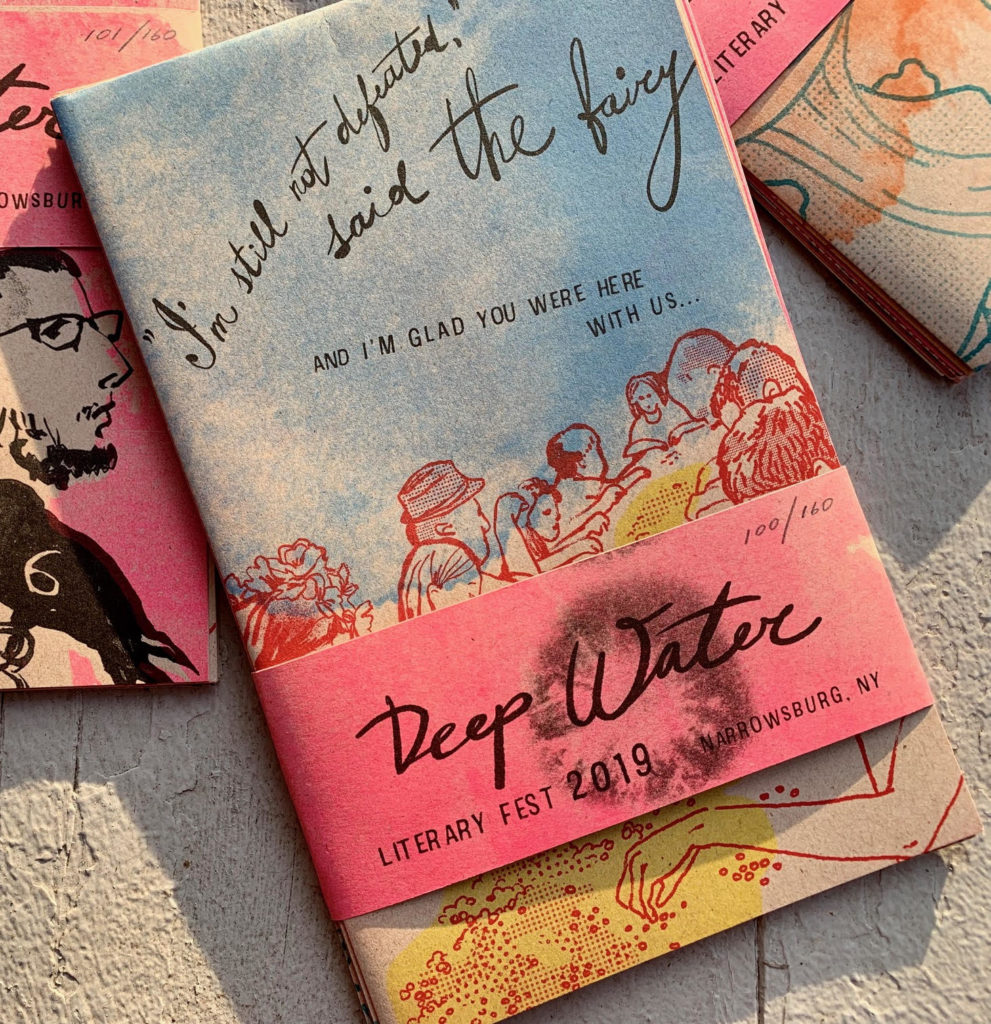

Dasha frequently uses a Risograph to create her art, and if you don’t know what a Risograph is you’re probably in good company. You can find more on that here. When, in 2018, I put together the inaugural Deep Water Literary Fest, Dasha came to multiple events and created a series of images from the performances and readings she attended. The following year she created a multiple-page memento of the festival complete with fold-outs that captured specific moments, like the musician David Driver performing a cover of “What the World Needs Now” during the opening night dinner. Last week, her festival book was chosen to be included in American Illustration 39, an annual compendium of the best artists in the field.

How do people end up where they do? When people ask how I ended up opening a bookstore in this town of 431 (the 2020 census may change that), I respond flippantly that I threw my hat in the air to see where it landed, but even as a metaphor it’s not quite true. My in-laws live 40 minutes away, and I had a passing familiarity with the area (if not the town), but I was sold on my first visit, largely on the charm of the Delaware River, around which the town snakes. We have rivers in Britain that would never make the grade in the U.S., where the rivers are wide and majestic. From the shop window I will occasionally spot a bald eagle as it swoops down to the water and back up, carried on the eddies of air. And where else can you stop for a dip in the river before opening up a bookstore?

Although Narrowsburg is tiny, truly a one stoplight town, it seems to have a magnetic pull that brings in the most interesting people. Dasha (who lives in nearby Hurleyville) is among them. She moved up here shortly after the September 11 attacks in 2001. Married, with a newborn, it made sense to be well away from the acrid smoke and fear of New York. But her actual story starts in Saint Petersburg, where she was born in the same apartment that her grandmother survived the Siege of Leningrad, the subject of a graphic novel that Dasha has written and will one day publish. Like so many people she owes her calling to an observant teacher who, spotting her talent, called her mother to the school and strongly suggested that Dasha be sent to a special art school. Her mother took the advice. “That girl disappeared, but she was like a guardian angel in the form of a teacher,” Dasha recalled. Four years later she moved on to what she called an “art high school,” one so old and prestigious that it was founded by Catherine the Great. She hated it. “It was so rich in history that there was no room for new ideas,” said Dasha. “They trained us like shoemakers – everything was about the craft, nothing about thinking. I didn’t know anything else, since I wasn’t from an artistic background, and knew no underground artists. They absolutely killed any creativity in me.”

What reignited her creativity was moving to New York, hot on the heels of the 1991 putsch when Boris Yeltsin memorably stood on a tank defying an attempted coup, while Gorbachev was being detained during a trip to the Crimea. Dasha was in St. Petersburg, and joined the pro-democracy protests, but left shortly after to visit an old friend from art school who had moved to New York. She recalls knowing she found home even as the airplane circled above the city.

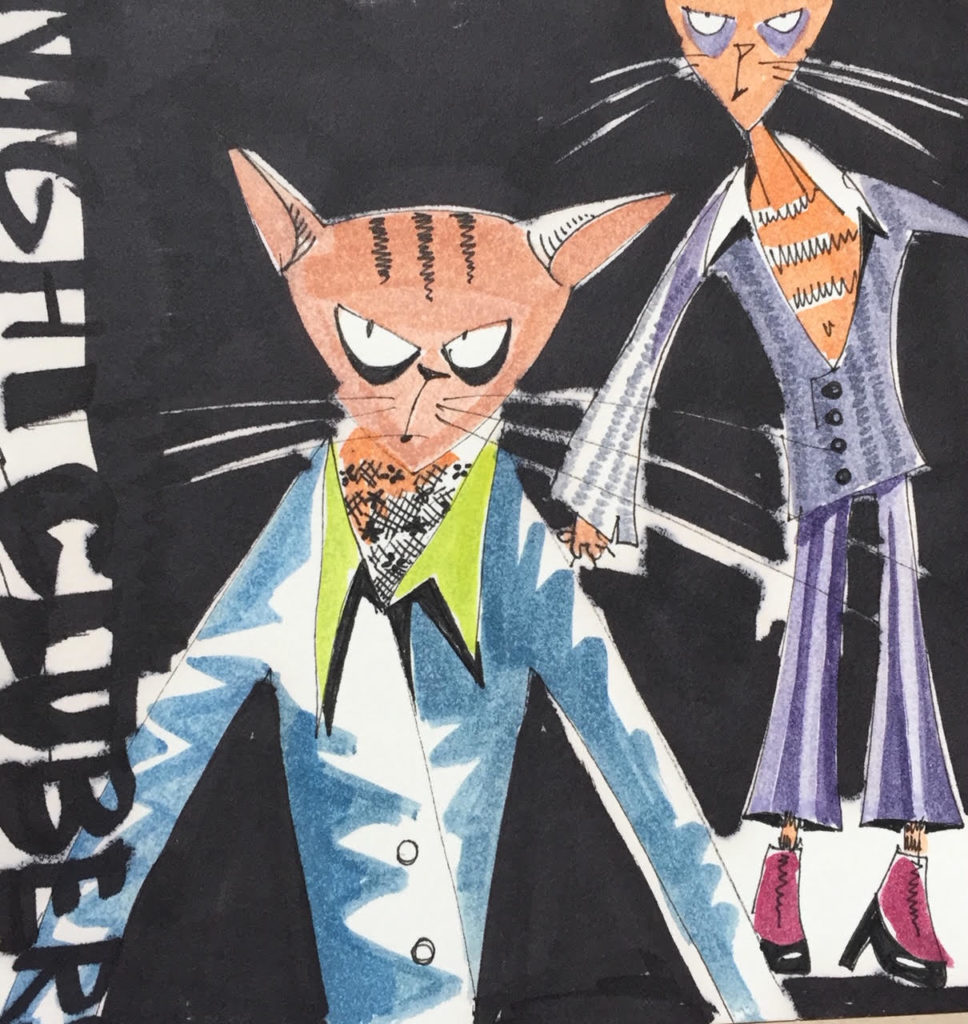

In New York Dasha hopped from gig to gig–computer animation, graphic design, textiles–until one afternoon in Barnes & Noble she had an epiphany. “Suddenly I saw a Maira Kalman book, Max the Dog, and it blew my mind,” she said. “It was the first time I realized what a children’s book could be, so I created my first children’s book, Crispin the Terrible.” The book, about a snotty cat with text by Bob Morris, was published, and several more after it. She had a baby, and her art changed. “I started to create very strange drawings of people shedding blood, eviscerations, really disturbed pictures,” she recalls. She submitted her work to a gallery in Chelsea, New York, that immediately offered to represent her. “I think I had a lot of beginner’s luck,” said Dasha. “I thought everything was easy: you write a book, you get a publisher, you submit something to a gallery, it agrees to represent you.”

Nothing, of course, is easy. Or not for long. When Dasha began homeschooling her son, her art work took a hiatus. And despite her love of New York, she never lost the sense of being an outsider. “I had a lot of luck at the beginning but this luck did not translate into a career,” she said, not with self-pity, but as a simple fact. “I didn’t understand what to do with this luck.” But she has finished homeschooling her son, and all that energy is now being channeled into her art again. In 2016, and again in 2019, she was accepted for a retreat at The Cabins, in Norfolk, Connecticut, set up by the writer Courtney Maum. She launched Real Time in Ink, which she describes as “an ongoing sketching project that focuses on travel, events, and cultural and political gatherings.” Her sketches, often on recycled paper or old books, have a wonderfully loose and fluid style, as if she is letting the pen lead her rather than the other way around. “I am a daydreamer,” she said. “A lot of my stories come while I take a hike or a walk. It’s like a movie in my head; it unrolls into an absolutely crazy story. And I get emotional, I can cry over it.”

As a young woman, studying chemical engineering in Leningrad, Dasha’s mother succumbed to similar flights of imagination. Far from home, where her younger brother lived with their mother, a geologist, in the vast wilderness of the North Pole – in Chukotka to be precise – Dasha’s mother succumbed to fearful visions. “There was a little aerodrome nearby and for some reason my mother started imagining that a small plane would fly over the yard, and crash on top of her little brother,” recalled Dasha. “She started crying uncontrollably. People started asking what had happened, but she was too embarrassed to tell them.”

It is, of course, a story about the power of imagination, and what we can achieve when we harness it for art. When we began chatting I asked Dasha if she considered herself an artist or a comic book creator. She gave the question some thought, and then answered: neither. “Actually, what I think I am is a storyteller,” she said. “I just use a different media to tell my stories.”

You can read more on Dasha Ziborova here.