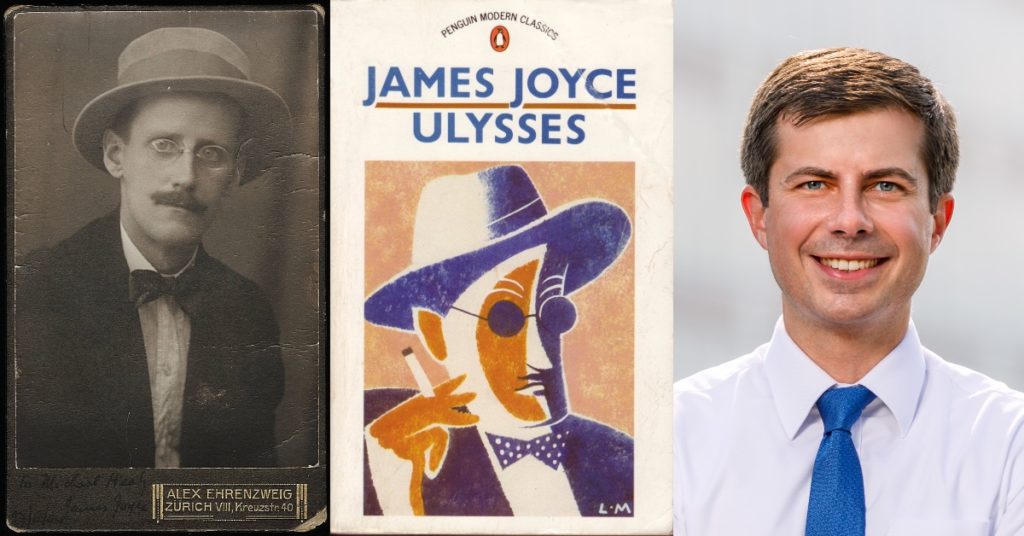

If Peter Buttigieg was only the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, Twitter would care less about what he reads. But he is running for the highest office in the land, and that makes a difference.

Aaron Hicklin

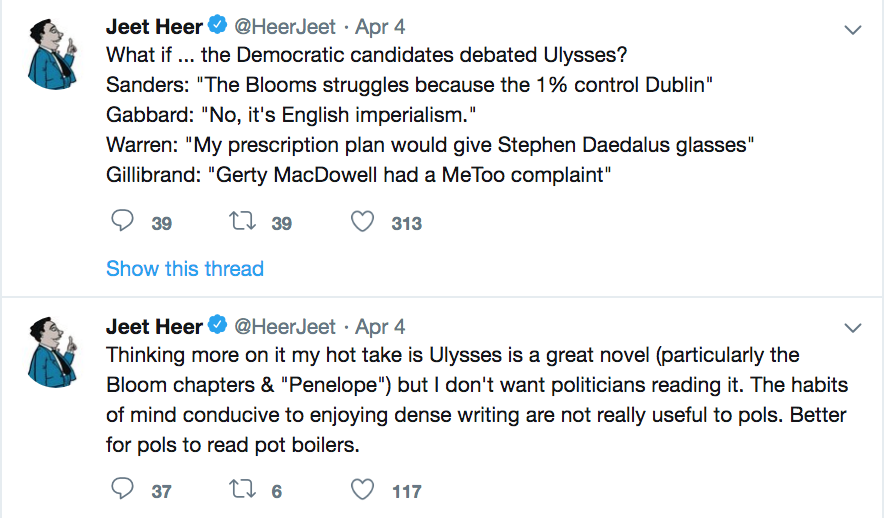

People love lists almost as much as they love to hate them. Take our latest, by the Democratic candidate for President, Pete Buttigieg. I was heading to LAX airport to catch the redeye last Thursday when I noticed some unusual activity on Twitter. Many of the people in my feed were tweeting about Ulysses, the novel that is widely considered a cornerstone of modernist literature, and which Buttigieg had just selected as one of his ten favorite reads for One Grand Books. “James Joyce is trending, so I have to give Pete Buttigieg credit for that,” tweeted Jeet Heer, a contributing editor for The New Republic.

Indeed, Ulysses was trending, but not entirely in a good way. A tweet by @HalpernAlex was typical in tone: “James Joyce is overrated and Pete Bottygeek (sic) never read Ulysses because no-one has ever ready Ulysses.” This kind of disparagement is common with canonical books. The not-at-all-subtle suggestion was that Buttigieg was grandstanding, and probably lying. But this is a candidate who learned Norwegian in order to read books by Loe Erland, so the idea that he’d be posturing seems far-fetched. Why do we find it so hard to believe that people like “difficult” novels? To quote Jessica Ritchey (@Ruby_Stevens), “What if it was possible to like old, challenging, obscure, or otherwise ‘difficult’ art, whatever you take that to mean, because you’re trying to pull a fast on anybody. What if!”

Although I have not read Ulysses, the reaction of Twitter, primarily from self-styled progressives, reveled in a smug anti-intellectualism that has roots in the endless conversations of the 1980s about “high” versus “low” culture, on whether, for example, the Beatles were better than Mozart. There is good reason for this—an appreciation for complicated art like Ulysses seems to depend on a privileged education—but would Twitter be happier if Buttigieg had told the world his favorite book was Murder on the Orient Express? Christie’s casual xenophobia aside, quite possibly. As it happens, John Lanchester wrote a stimulating essay for The London Review of Books making the case that Christie was a great modernist writer alongside Joyce and Virginia Woolf. This is a stretch, but I happen to adore Christie, in part because I love the tropes of her mysteries, even though I’d probably think twice before elevating her to one of my ten favorite novels.

Still, few of our curators choose mystery or spy novels (Tom Hanks is an exception), and this gets to why such lists arouse suspicion. For Emily Nussbaum, the New Yorker critic, Buttigieg’s choices can’t entirely be trusted. “People know how to fake for these lists,” she tweeted last Thursday. “Yes, I’d love a leader to have great taste that shows off their excellent values. But I mainly want them to get elected and make change. Some terrible people like excellent books.” Is Nussbaum right? After all, to what purpose had Buttigieg faked a list that had merely infuriated most people, either because he made the mistake of loving Ulysses, or for naming only one book by a woman—Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. That some of these critics were arguing, in the same breath, that Buttigieg’s book choices were contrived showed how facile the debate had become. It takes a perverse act of cynicism to dismiss such lists as inauthentic while at the same time demanding curators be inauthentic by choosing books that reflect a more expansive world view. If such lists weren’t often faked in the past, social media will do its best to change that.

Still, few of our curators choose mystery or spy novels (Tom Hanks is an exception), and this gets to why such lists arouse suspicion. For Emily Nussbaum, the New Yorker critic, Buttigieg’s choices can’t entirely be trusted. “People know how to fake for these lists,” she tweeted last Thursday. “Yes, I’d love a leader to have great taste that shows off their excellent values. But I mainly want them to get elected and make change. Some terrible people like excellent books.” Is Nussbaum right? After all, to what purpose had Buttigieg faked a list that had merely infuriated most people, either because he made the mistake of loving Ulysses, or for naming only one book by a woman—Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. That some of these critics were arguing, in the same breath, that Buttigieg’s book choices were contrived showed how facile the debate had become. It takes a perverse act of cynicism to dismiss such lists as inauthentic while at the same time demanding curators be inauthentic by choosing books that reflect a more expansive world view. If such lists weren’t often faked in the past, social media will do its best to change that.

Perhaps there is a certain level performance in creating a list of ten favorite books, but if so it is still likely to reflect something true. Just compare books chosen by Tilda Swinton to those selected by Tom Hanks or Roxane Gay. Many of Gay’s choices are by women of color (she also makes rooms for Edith Wharton), while Hanks is big on history. Swinton opts for Scottish poetry, Nancy Mitford, and Auntie Mame. Do those feel contrived to you? Meanwhile, had Buttigieg wanted to impress his potential voters, would he have chosen nine titles by non-American writers (the exception was Armageddon Averted by Stephen Kotkin, a non-fiction account of the collapse of the Soviet Union)? And it’s hard to fake books one loved in childhood. Buttigieg chose A Child’s Christmas in Wales by Dylan Thomas, and The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, a book that has several other fans at One Grand Books, but which is unsettling and deeply sad. As a story of exile, it is also a book that has long resonated with queer children.

And that brings us to the most obvious absence on Buttigieg’s list. None of his choices appear to reflect his experience as a gay man. Or do they? In all the drama over Ulysses no-one mentioned one other startling element of a novel now nearing its 100th anniversary: how queer it is. While some have suggested that Molly Bloom reflects a classic gay diva, the book also involves gender swapping and repeated references to Oscar Wilde, while Leopold Bloom is oddly androgynous, the antithesis of the hard-edged masculinity of much of Irish literature.

At this point, let’s just note that for politicians the stakes are always high. Other contributors to One Grand Books, including the novelists Irvine Welsh and Bret Easton Ellis, have chosen Ulysses without blowback. But they are not politicians, they are writers, and therefore allowed to like “difficult” things. Context is everything. If Buttigieg was only the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, Twitter would care less about what he reads. But he is running for the highest office in the land, so every utterance is parsed for implication. Lists are easy to denigrate because they set up simple binaries. If you’ve read it, you either hate or you love Ulysses, and if you haven’t you either love or hate what it stands for. All you have to do is broadcast that on Twitter, and let the fireworks begin. As Boris Kachka, the books editor at New York magazine observed simply (and correctly), “Sometimes lists are good at starting conversations. That’s all.” Amen to that.

This is so smart and thoughtful. Thank you.

I will add that he also included titles he read in the original Arabic and Norwegian–two of many languages he’s fluent in. That seems to be getting lost in this discussion.

Finally, backlash is boring.